展期 Period:

2025.3.20—2025.5.30

艺术家 Artist:

曾建颖 Tseng Chien-Ying策展人 Curator:

王乙竹 Wang Yizhu

地点 Venue:

Longlati经纬艺术中心 Longlati Foundation

前言 Introduction:

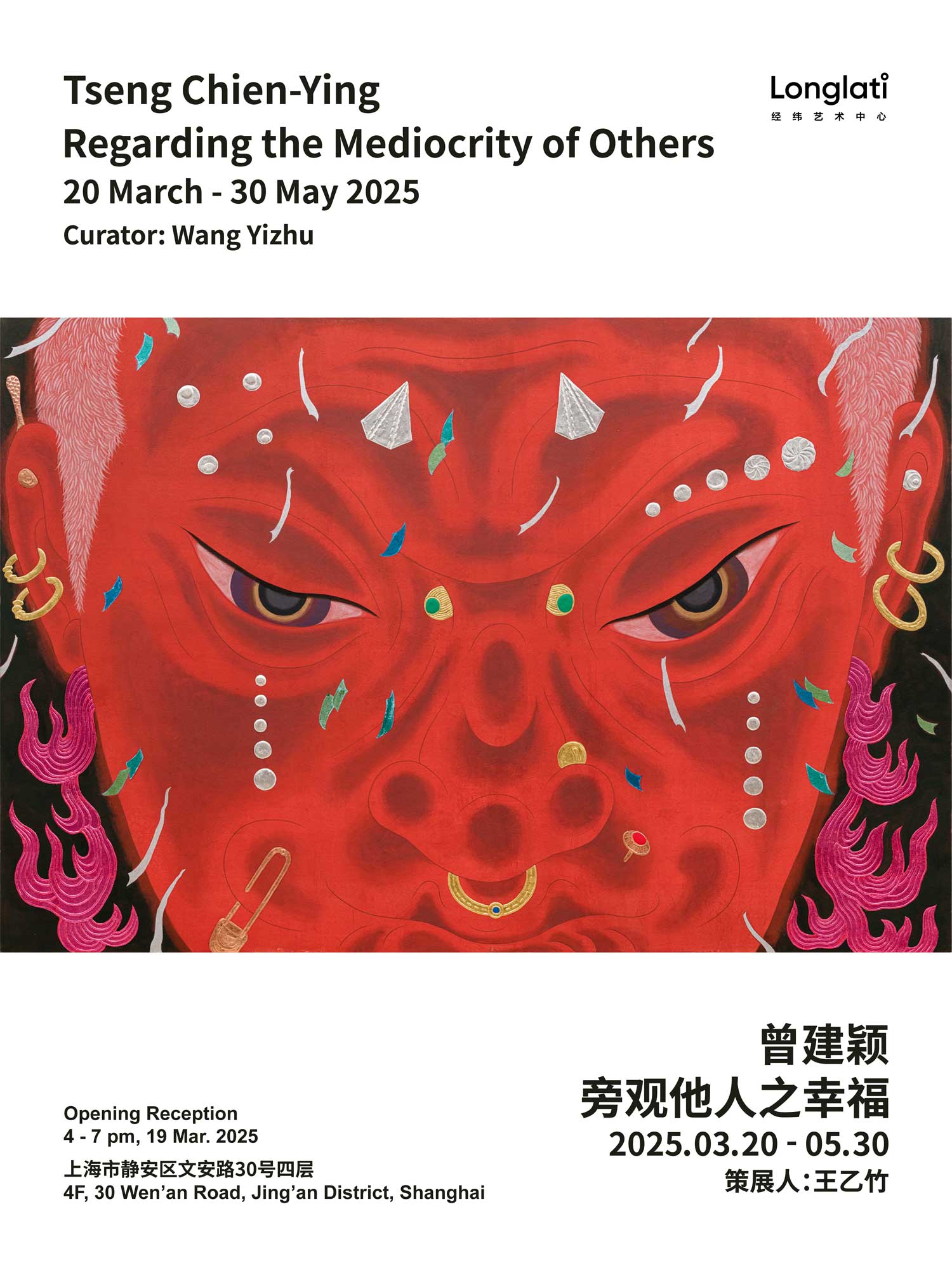

Longlati经纬艺术中心欣然宣布将于2025年3月19日呈现曾建颖(b.1987)个人展览“旁观他人之幸福”。本次展览遴选其近年完成的十六件作品,通过工笔技法与胶彩媒介的结合,以细腻笔触与隐喻意象展开对肉身欲望与心理诉求的双重探索,并借视觉叙事勾勒出集体潜意识中的某种精神侧写。

展名的提法源于苏珊·桑塔格(美国)2003年的著书《旁观他人之痛苦》,桑塔格在书中指出:“摄影把一切客观化,将某人或某事转化为可占有的物件。而照片如同某种炼金术,因其被珍视为现实的透明观照。”她警示,当苦难沦为被消费的影像时,观看可能滋生冷漠而非同情,并质疑这种观看能否真正推动改变。在此理论脉络下,曾建颖提出思考:若创作实践聚焦于日常(司空见惯)行为是否也能唤起画面主体为“旁观者”所带来的另类遐想?

群体互娱时,吸烟已成为人与人建立联系、寻求归属的隐性媒介。点燃香烟的瞬间、烟雾中的目光交汇、吞吐间的无声交流,此类散发的肢体动作,最能映射出都市人群的心理诉求与社会互动。曾建颖创作的《取火》(2022),画中人物点烟的动作既像个体对社交归属的主动寻求,又像群体对身份认同的无意识应对。吸烟社交或许并非真正意于建立深度联系,更像一面《棱镜》(2024),用近乎表演的镜像动作去观察他人的存在,并确认自身在社会空间中的位置。同样,当缀饰不再单一地附庸于身体表面,而是刺入肌肤,珠宝手饰便早已超越了单纯的装扮意味。采用“盛上”技法的《森罗》(2024)系列,颜料与金属箔的逐层堆叠给予缀饰很强的立体感,使镶嵌焕发出新的语言。所谓“华丽的疼痛”却成了都市亚文化青年寻求认同的标志:穿刺的瞬间突破身体界限,缀饰作为引线针,他们通过痛感建立起社群纽带。当金属的冷峻与身体的柔软并置时,他们追求个性独立却依赖集体认同,渴望浮夸表达又借机维系起情感链接。

自2010年起,曾建颖开展了“千手计划”,手的意志在此得以更广泛的延展。拈花惹草本意指指尖轻掠花叶,如今却化为都市的欲望。《捻花》(2024)与《踏青》(2024)两组双联屏在他执笔下结合了中国画的“白描”线写与佛教画的“凹凸法”皴染,巧妙地消融了视觉上的轻重主次,使画面更具流动性与开放感。手在试探、采撷、攫取,又在犹豫松开;脚在游走、踏过、寻觅,却也错过迷失。久驻于都市的霓彩与风花雪月的相逢后,手与脚是被欲望驱使的工具,在触碰与踩踏间诱导观看。在借鉴日本“美人画”后,《胭脂》(2022)与《夕阳无限好》(2024)直指女性阴柔如何抵抗传统的美人意象——眼睑低垂的疲惫感,唇角下置的苍老态,将美人画中的氤氲转化为女性独有的阴性美。当消费审美对“女性凝视”还在期待时,作者已揭开观看与被观看之间的权利关系,迫使观者意识到自身的观看行为。观者在“观看”与“被观看”间徘徊,暗合了 “旁观者”在卷入与逃避的心理,也最终指向身份的多重矛盾。

在“旁观他人之幸福”中,我们不再将“幸福”简单归于褒义词性,而是尝试剥离其固有的情感色彩,使其呈现出一种更为平淡的语义。展览空间将“旁观”转化为深入其中的参与,“幸福”便不再仅作固定的结果,而是局内人与局外人间生成的流动体验。

##Pagebreak##

Longlati Foundation is pleased to announce the solo exhibitionRegarding the Mediocrity of Others by Tseng Chien-Ying (b.1987), which will open on March 19, 2025. The exhibition features 16 recent works by the artist, which combines the brushwork and gouache medium. The works explore the dual dimensions of physical desire and psychological longing through delicate strokes and metaphorical imagery and employ visual narratives to sketch the spiritual contours of the collective unconscious.

The title of the exhibition is drawn fromRegarding the Pain of Others (2003) by Susan Sontag (U.S.). “PHOTOGRAPHS OBJECTIFY: they turn an event or a person into something that can be possessed. And photographs are species of alchemy, for all that they are prized as a transparent account of reality” (Sontag, 2003). She warns that when suffering is reduced to consumable images, viewing may foster indifference rather than compassion, and questions whether such viewing acts can truly drive change. In this theoretical context, Tseng raises a thought: If artistic practice focuses on daily actions, can it also evoke alternative reveries inspired by the “onlooker” that the subject of the image brings about?

In settings of group entertainment, smoking has become an implicit medium to establish connections and seek a sense of belonging. The moment of lighting a cigarette, the gaze met in the smoke, and the silent communication between inhales and exhales most vividly reflect the psychological needs and social interactions of urban dwellers. InThreesome (2022), Tseng portrays the act of lighting a cigarette as both an individual’s conscious pursuit of social belonging as well as a group’s unconscious response to identity recognition. Smoking as a social act may not necessarily aim to forge deep connections. Rather, it’s likeSpectrum (2024), where mirrored, almost performative gestures serve as a mean to observe others’ presence and affirm one’s own position within social space. Similarly, when adornment is no longer merely an accessory on the body’s surface but instead pierces the skin, jewelry and ornaments transcend mere decoration. In theBystander (2024) series, the Moriage technique is leveraged. Meanwhile, the layered application of paint and metal foil lends a strong sense of dimensionality to the embellishments, giving inlay a renewed visual language. The so-called “glorious pain” has become a symbol of identity for urban subculture youth: the moment of piercing breaks the boundaries of the body, and adornments serve as guiding needles through which they forge communal bonds via the sensation of pain. When the cold rigidity of metal is contrasted with the softness of the body, they strive for individuality yet rely on collective recognition, crave extravagant expression, and meanwhile use it to maintain emotional connections.

Since 2010, Tseng has been developing theThousand Hands Project. Here, the will of the hand is extended more broadly. The phrase picking flowers and touching grass originally referred to fingertips lightly brushing against petals and leaves. However, in an urban context, it has transformed into a metaphor for desire. In two diptych series ofGive or Take(2024) andStampede (2024), Tseng seamlessly integrated theBaimiao linear technique of traditional Chinese Painting with theConcave-convex shading method found in Buddhist Art. This fusion not only subtly dissolves the visual hierarchy of weight and prominence, but also lends the compositions a greater sense of fluidity and openness. Hand is probing, plucking, and grasping while hesitating and releasing. Feet are wandering, treading, and seeking while also missing and losing their way. After prolonged immersion in the neon glow and fleeting romances of the city, hands and feet become tools driven by desire and guide the act of looking through touch and transgression. Drawing inspiration from JapaneseBijin-ga,Blush (2022) andSunset Soda (2024) directly confront how feminine softness resists the traditional imagery of beauty. The drooping eyelids, evoking exhaustion, and the subtly downturned lips, suggesting aging, transform the ethereal aura ofBijin-ga into a distinctly feminine, negative aesthetic. Although the commodified ideal of beauty still anticipates the “female gaze,” Tseng has already exposed the power dynamics between seeing and being seen. This compels viewers to recognize their own act of looking. In this interplay of “watching” and “being watched,” the viewer waver, which mirrors the psychological tension of the onlooker caught between engagement and detachment, and ultimately points to the multifaceted contradictions of identity.

In the exhibition,“Happiness”is no longer simply regarded as a positive notion. Instead, we attempt to strip it of its inherent emotional connotations and render it in a more neutral and subdued semantic form. The space transforms“Regarding”into deep participation, in which“mediocrity”is no longer a fixed outcome, but a fluid experience shaped between insiders and outsiders.