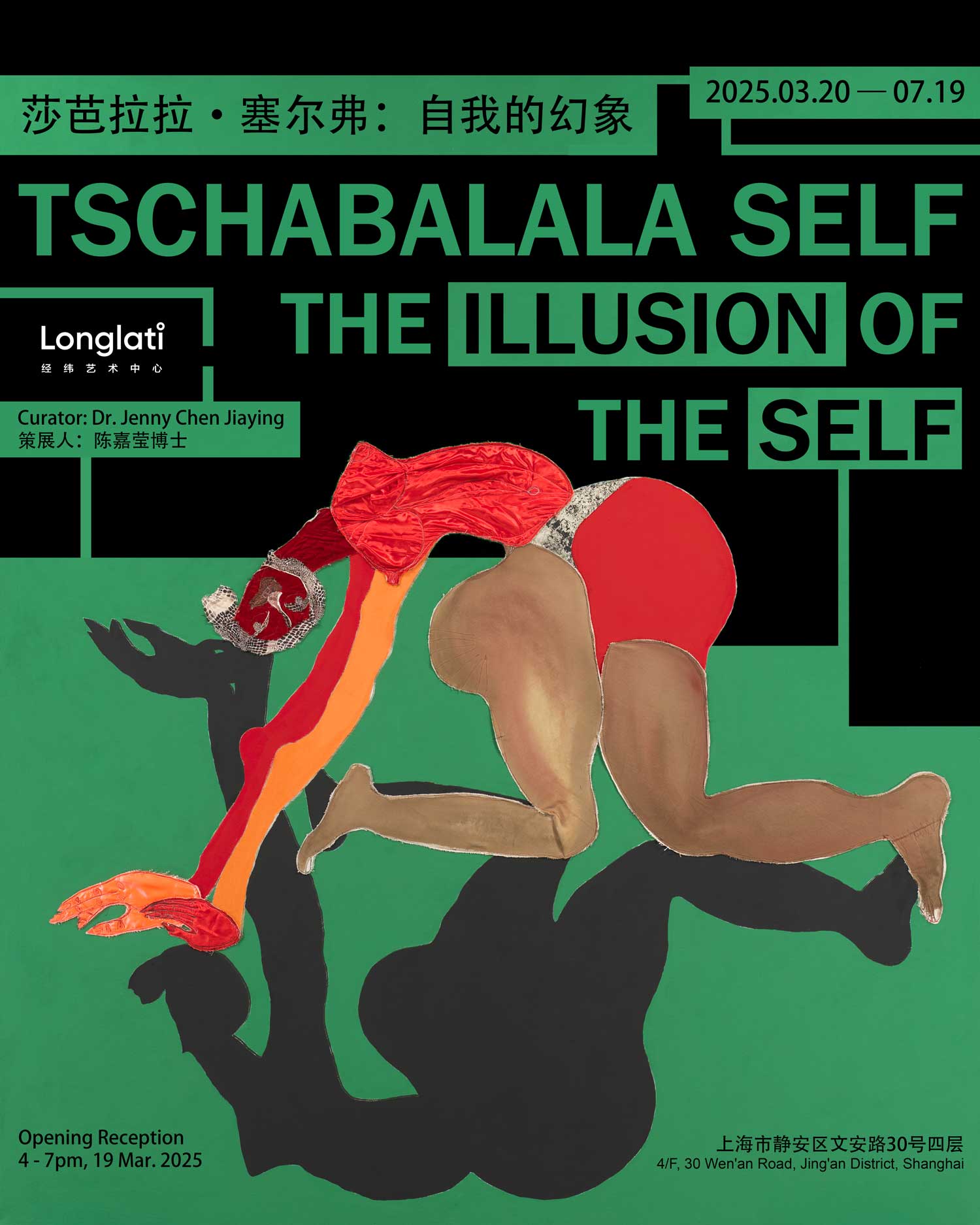

The extent to which the “self” is a fabrication of power discourse, a remnant of collective consciousness, or an illusion woven under the name of “I”—how do these questions enter the inner world, infiltrate private spaces and penetrate the dreams that soak them? The exhibition “The Illusion of the Self” by Tschabalala Self (b.1990), opening on March 19, 2025, at the Longlati, serves as a case where these inquiries are transformed into an inward exploration. After seven years away from China, Self will present nearly twenty cross-media works, including mixed media paintings, immersive installations, musical video works, and “furniture,” creating spaces that cut-and-mix dream and reality.

Born in Harlem, New York, Self’s work is infused with the vibrancy of the Harlem Renaissance—its dance, music, and the exploration of the Black body’s existential experience in constrained spaces and times. Through unconventional collage techniques, combining paint, fabric, and discarded canvas fragments, Self creates a unique diaspora aesthetic. This hybrid grammar not only challenges mainstream cultural stereotypes of Black female bodies but also deconstructs outdated narratives in art history related to race and gender. Knitting and sewing in the diasporic history of Black people is both a material form of labor and a metaphorical cultural stitching. Personal and collective, ethnic and cultural, aesthetic and social, gender and desire—all these elements are intertwined in physical practice, forming intricate silhouettes of brocade.

Self’s creative inspiration also draws from her observations of everyday life and cultural scenes. For example, her recent exhibition “Around the Way” (EMMA - Espoo Museum of Modern Art), named after a term from African American vernacular, refers to individuals embodying their community’s culture. Another example is her 2016 exhibition “Bodega Run”, first shown at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles and later at the Yuz Museum in Shanghai. In this project, she transported the corner bodegas—small, family-run grocery stores catering to minority communities from New York—into the art museum space. In her encounters with objects, Self improvises using their aesthetic elements, including different textures and clothing patterns, to construct new narratives about layered diasporic identities and Black femininity. This approach not only responds to Black feminism’s emphasis on “intersectionality” but also dismantles the single-identity logic and flattened historical narratives of Western art discourse while attesting to the transformative power of diasporic experience in visual culture. The Black body dances in vivid hues like Matisse’s, and the collage of fabric and hybrid aesthetics bursts into life, cleverly reflecting multidimensional cultural identities and sensible distribution, bringing forth a new “self” that leaps from the canvas. This carnival of fabric and color not only subverts traditional representations of Black female figures but also celebrates the liberation of the multiplicity of subjects.

The exhibition is also connected to hidden desires beneath the“illusion of self.”On one hand, the female figures referred to by Self are always contending with expectation and projections of the other, yet they are liberated from these expectations. The latest work,The Voyeur, reflects her contemplation of the male gaze through themes of sex and the technique of fabric Cubism. The female illusion that shadows the painting obscures the vibrant colors, embodying the civilisation and its discontents of sexuality. On the other hand, these desires resonate with the dreamlike whisper lingering in“home.”The enduring presence of the domestic environment in Self’s works, rooted in her sensitivities towards the boundaries between public and private spaces, also refers to the inner circle contoured by the body. Unarticulated clues combine to form a complex emotional puzzle: projections on the body, consciousness drifting outside the bodily form, patriarchy within the private domain, the female body being displayed and exhibited, the vanity and the fall of love—all entangled in romantic silk, interweave the“illusion”of self, home, and place. It is the life world and subject shape projected by a Black woman growing up in a cross-racial, urban melting pot, that is sensually real, but also imagined.