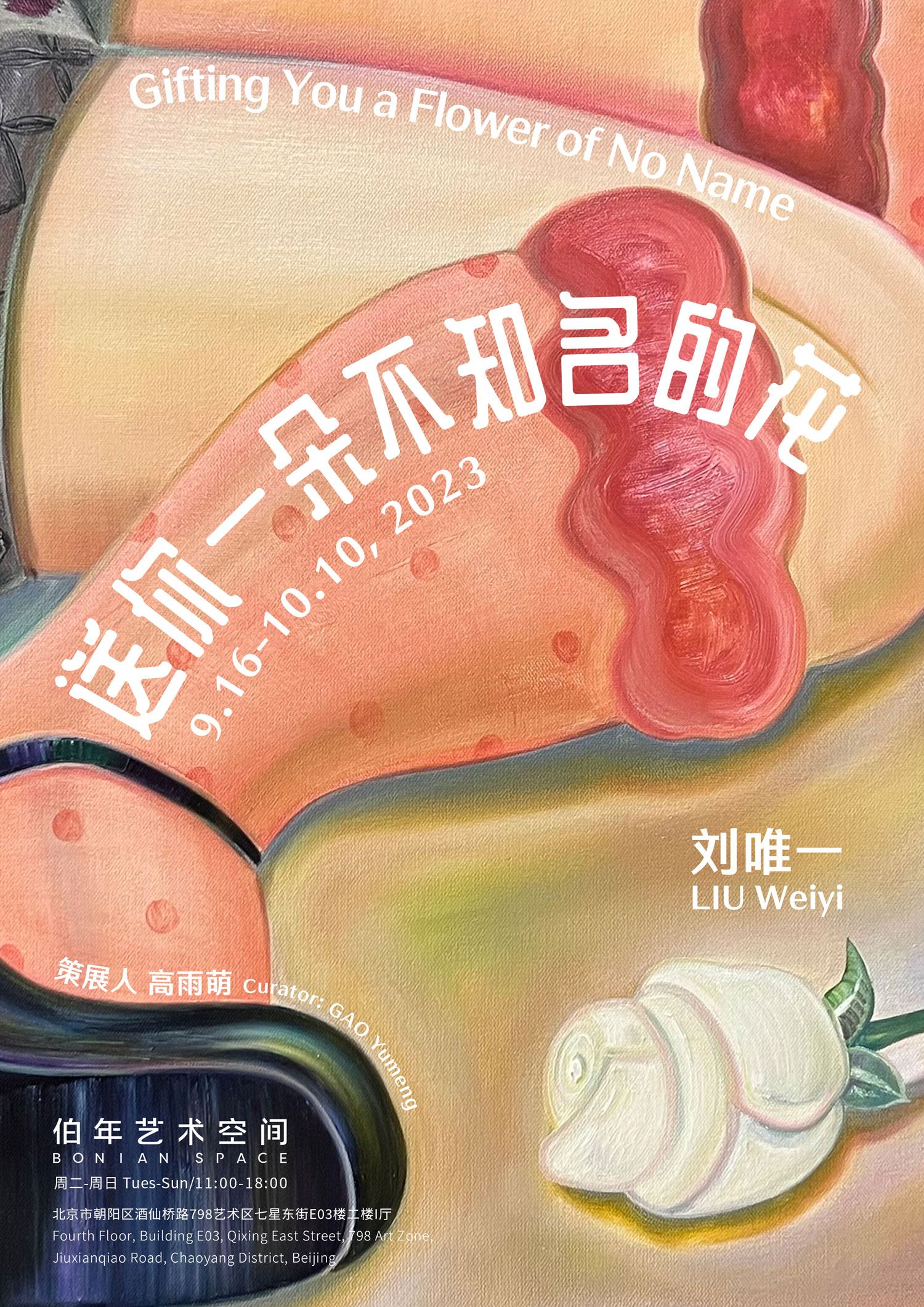

BONIAN SPACE is pleased to announce the upcoming solo exhibition of artistLiu Weiyi, titled "Giving You a Flower of No Name," which will be on display from September 16 to October 10, 2023.Curated by Gao Yumeng, the exhibition will feature over twenty of the artist's latest paintings.

A century ago, British novelist Virginia Woolf penned the line, "Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself." The moment she steps out the door, the catalyst of stream-of-consciousness is activated, and her thoughts return to Clarissa at the age of eighteen. Flowers are often used to symbolize women's beauty, purity, and fragility. Clarissa's choice to "buy the flowers herself" is a rejection of passively accepting this cultural symbol. Instead, she actively defines and controls it, using what is considered a "male" economic bargaining chip to acquire the "flowers," thereby empowering women's economic and emotional autonomy.

The title of this exhibition, "Giving You a Flower of No Name” is also the name of Liu Weiyi's work. In the symbolic system constructed by society, "flowers" serve as a metaphor for love, and "giving flowers" acts as a token for conveying desire. When the subject of this action is directed towards women, it disrupts the traditional gender dynamics and role expectations, liberating women from the passive gaze and objectification of desire, and transforming them into active agents. Liu Weiyi continually explores ways of self-representation within an image system replete with paradigms that shape the body. She situates the body in an open context of perception, where the boundaries between the part and the whole, individual experience and aesthetic universality, and subject and object, become blurred and fluid. In her work, the body ceases to be an object observed and defined by others; it becomes the protagonist in its own narrative of self-recognition and self-expression.

This transformation in subjectivity is not merely about the construction of the self; it also encompasses external recognition. It not only points to the artist's individual actions and creative posture but also addresses broader questions and responses concerning human experience in both art and society. The more proactive and dynamic perspective exhibited in Liu Weiyi's paintings inspires viewers to transcend the barriers of gendered gaze and narratives imposed by others, allowing for a freer acceptance and expression of body and desire. And this time, there's no need to accidentally step into a giant footprint or to blindly lie on a stone bed waiting for a kiss. The exhibition invites us to engage with art and society on our own terms, challenging us to redefine traditional roles and expectations. It serves as a call to action, urging us to take control of our own narratives, to question societal norms, and to engage more freely with our own bodies and desires.

Localized Perspectives and the Gaze

Liu Weiyi often approaches the sculpting of the body from a "localized" perspective. Stemming from her own bodily experiences and emotional memories since childhood, the limbs of her characters often possess a form that diverges from mainstream aesthetics—swollen yet solid in their physical features. At the outset of this series, she starts from a female perspective of self-observation, subtly transgressing socially constructed aesthetic standards and thereby challenging the authority of mainstream beauty. Bursting buttons, deformed shoes, and shoulder straps that leave marks—these intimate moments of discomfort are presented by the artist in a calm and slightly humorous manner, alleviating the anxiety and inadequacy brought about by the absence of an ideal body under social scrutiny.

In Jacques Lacan's theory of the "Mirror Stage," infants form a preliminary self-awareness by observing themselves in a mirror. This self-awareness is incomplete and fragmented but eventually gets integrated into a larger symbolic order. The "Big Other" is a complex structure encompassing society, culture, and symbolic order, identified by the individual, which shapes their identity and desires. Within this order, women are often seen as objects of desire, defined and limited by the male gaze. This gaze from men not only objectifies women but often leads them into the trap of self-objectification, making it a part of their self-assessment and self-awareness. Liu Weiyi's focus on the localized aspects of the body concerns the formation of the subject and also explores the position and meaning of these bodily elements (or individuals, in a broader sense) within a larger symbolic network. In her interaction with the "Big Other" of social aesthetics, she continually constructs and reconstructs her sense of self.

This introspection is not isolated but manifests and evolves within the dynamic tension of interactions with men, objects, and the world at large. In her recent works, Liu Weiyi gradually moves away from the transformation of bodily experiences and memories, shifting her focus to the functions and sensations that the body can present. Colors, intimately connected to individual emotions and states of mind, flow along the lines and curves of the body. The rich hues at the edges are like the glowing halo of consciousness, forming an atmosphere that is almost tangible. Through the focus and magnification of localized areas, the body further departs from its inherent appearance in the processes of overlapping, deformation, and abstraction, thereby presenting an increasingly solid and stable posture.

The bodies depicted by Liu Weiyi are not confined to a static, objectively presented entity; rather, they represent a subjective, diverse, and fluid experience. She is not recreating a body that exists in time; instead, she portrays a body that lives within specific contexts, emotions, and states of consciousness. Under the visual strategy of exaggerated magnification, these localized body parts are no longer merely objects to be viewed and defined by others; they become subjects of self-awareness and self-expression. In her attempt to deconstruct the objectifying gaze, the artist gradually progresses from a reflection on self-discipline to self-identification, and then to a transformation towards self-appreciation and admiration of the body.

High Heels and Body Techniques

High heels are one of the most common bodily markers in the female figures depicted by Liu Weiyi. The different colors, styles, and intricate decorations are not merely for the sake of visual richness or to portray a certain physical beauty. Behind them lies a complex interweaving of gender roles, bodily discipline, and bodily liberation.

The role and significance of high heels have undergone subtle changes throughout history. In medieval times, both male and female nobles were fond of wearing the precursors to high heels—wooden clogs known as "pattens"—either to avoid muddying their shoes or to compensate for a lack of height. With the unfolding of the "Great Male Renunciation" during the Enlightenment era of the 18th century, men abandoned high heels in a bid to champion rationality and pursue practicality. However, they left high heels as a marker of gender segregation and stereotypes for women. As a result, high heels carried the patriarchal society's aesthetic demands and bodily discipline for women, long constraining women's control over their own bodies. Since the 19th century, as women's subjectivity has awakened, they have gradually become aware of their subordinate and objectified status relative to men in social contexts. In the process of striving to break free from this 'otherness,' high heels have become linked with the history of women's oppression.

However, the concept of the "body" is also constantly changing amid the upheavals of historical culture and social thought. Sociologist Bryan Turner places the "body" within the purview of consumerism, where people master "body techniques" through "consumer self" to signify their different identities and roles. In doing so, they shape and construct their own lifestyles within specific social and cultural contexts, validating themselves through a competitive public space.

"Today's history is a history of the body situated in consumerism, a history of the body being incorporated into consumption plans and consumption purposes, a history where power makes the body a subject of consumption, a history where the body is praised, appreciated, and toyed with." In this era that appreciates and focuses on the body, women are also gradually gaining control over their own bodies: they are no longer the 'other,' but a subject of experience and thought. Women have the right to make their bodies objects of autonomous consumption through high heels, thereby gaining confidence and power in the process of self-construction and self-expression through body techniques.

In the artwork titled "Multiple Identities," the artist Liu Weiyi employs a collage-like technique to assemble various symbols related to female identity and roles—diamond rings, baby bottles, handbags, cleaning gloves, kitchen utensils, and more. These symbols serve to mark women within the expectations of different life stages and social roles, creating a set of female figures entangled in a diverse array of experiences. However, Liu Weiyi does not merely accept or present these symbols at face value; instead, she situates them within an open, fluid, and even ambiguous context.

For each "identity," she pairs different styles of skirts and high heels. Sometimes these pairings align with the activities indicated by the symbols; at other times, they appear somewhat incongruous. For instance, the patterns on the dense stockings resemble varicose veins, a result of long-term fatigue; the cleaning tools in hand transform into ribbons wrapped around the ankle as the gaze shifts; and the kitchen utensils are placed in a handbag that represents fashion and "casual luxury."

From styles to materials, from scenes to preferences, the choices and presentations of clothing and accessories make these female figures more than just carriers of identity and roles. They also become creators and deconstructors of symbols and meanings. In continually questioning the symbols and designations that society imposes, they maintain a distance from the emptiness of mere symbolism.