Hunsand Space (Beijing) is honoured to present the photographic works of Zhou Zhenhua (1935–2023) on 15 March 2025. Born and based in Huixian, Henan Province, Zhou took up photography in 1968, creatively documenting the transformation and development of the region from the late 1960s through the 1990s. His images offer a comprehensive and vivid portrayal of life in Huixian, capturing large-scale efforts in land reclamation, mountain road construction, water conservancy projects, and the collective activities of rural institutions in education, culture, sports, and healthcare throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Alongside these, Zhou also preserved a rich visual record of the region’s cultural relics, natural landscapes, and human heritage.

Zhou’s Huixian, as seen through his lens, has long been of strategic significance throughout history. To the west, crossing the deepest gorge of the Southern Taihang Mountains, lies Lingchuan County in Shanxi—this route is Bai Xing (白陉). The Taihang Mountains, known as the "spine of the world," form a natural barrier between the North China Plain and the Loess Plateau. The Eight Passes of Taihang (太行八陉) were the ancient routes connecting Shanxi, Hebei, and Henan across these mountains. Guarding the eastern gateway to Bai Xing, Huixian has historically been a key site for economic exchange, military defence, and population movement, accumulating profound historical and cultural depth over three millennia. Today, many of its cultural relics, dramatic landscapes, and historic sites have been repurposed as tourist destinations. With time, history fades into the vast currents of change, while a new era reshapes Huixian’s identity—its landscapes and heritage now forming the city’s modern-day "calling card" to the world.

As a pivotal figure in Chinese documentary photography, Zhou Zhenhua exhaustively documented all aspects of Huixian’s production and daily life. His works hold irreplaceable historical and archival value, providing a visual corpus for studying Chinese society of that era.Beyond mere documentation, they confront viewers with an inescapable aesthetic particular to their time—rooted in the vast 'earth' itself. Zhou’s practice centered on capturing 'truth' in its natural state, fusing tension and narrative into a cohesive whole.

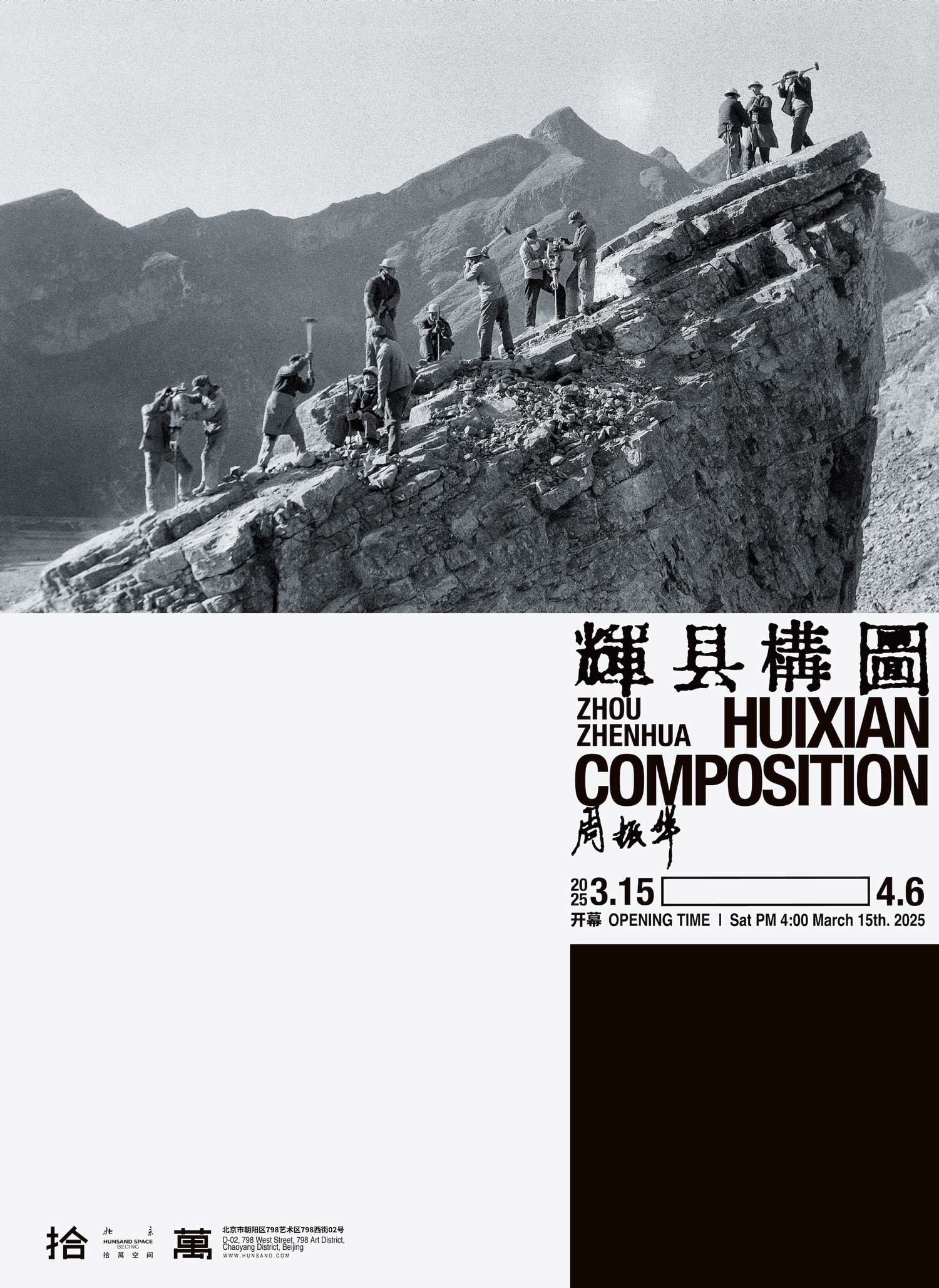

Working primarily with film and natural light, Zhou used contrasts of light and shadow, as well as sharp and soft focus, to emphasize his subjects and intensify the visual impact of his work. The human figure—particularly facial expressions and gestures—frequently serves as the focal point of his compositions, vividly capturing the spirit of the individuals and the era. His photographs transcend mere documentation; they inscribe the psychological weight of the time onto the unnamed yet vivid individuals who populate his frames. Compositionally, Zhou’s work prioritizes thematic expression, using the visual arrangement to convey conviction and hope. This formal approach goes beyond content, as it strives to achieve a harmonious balance between dramatic tension and narrative structure. At the same time, Zhou pays close attention to the aesthetic pleasure of form, deliberately drawing from the compositional sensibilities of painting, emphasizing the interplay of lines, light, and negative space to create a seamless integration of form and meaning.

Huixian was reclassified as a city in 1988, though it retained its county-level designation and administrative structure. Zhou’s photographs document a pivotal period in Huixian’s history, offering a panoramic view of county life in the early years of the People’s Republic of China. They capture the transition from an agrarian society to industrialization and economic modernization. Yet Huixian is not an isolated case—across the Taihang Mountains, more than 400 counties in Hebei, Henan, and Shanxi underwent similar transformations, though few have been recorded with such depth.

The 800-li expanse of the Taihang Mountains has witnessed millennia of human struggle—clashes, dynastic wars, and fleeting names lost to history. Today, Huixian and countless similar counties scatter across the land, their geographic spread and cultural relics telling their own stories. Yet, in the eyes of later generations, they often become mere reflections of history’s vastness, evoking nostalgia and imagination. Through Zhou’s lens, however, the ordinary and “real” individuals are captured—ancestors or those who lived through the era. While mere specks in the grand flow of history, these records allow us to momentarily escape from myth-making, offering a direct connection to a not-so-distant past, inviting us to reflect on where the “present” truly comes from.