展期 Period:

2024.7.20—2024.8.18

艺术家 Artist:

策展人 Curator:

地点 Venue:

前言 Introduction:

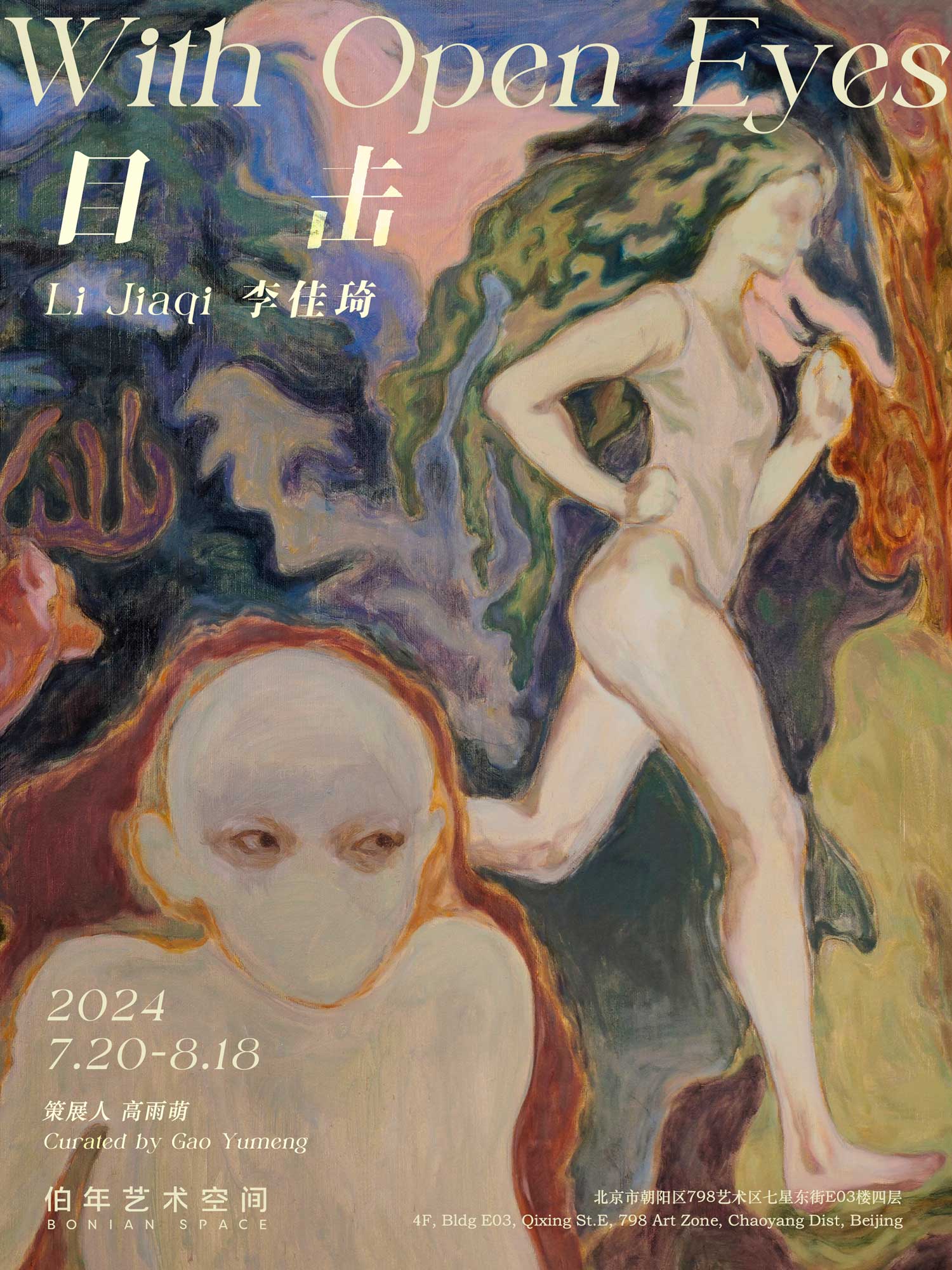

伯年艺术空间欣然宣布,将于7月20日至8月18日推出艺术家李佳琦的首个个展“目击”。本次展览由高雨萌担任策展人,集中呈现艺术家近年来创作的十余幅绘画作品。

“当你望向我时,我也会望向你,以同样的目光。”——李佳琦

凝视与回望

李佳琦的创作起始于“自我”在面对内在矛盾冲突与外部复杂环境时的处境与应对策略。她以流动的线条与色彩对潜意识世界展开象征性描绘,画面中的人物在来自外部的他者目光下剥离出多种形态的自我,孤立、悬浮、挣扎、逃逸,最终弥散入带有暗示性的虚构自然中。

然而,这种主体于复杂中的消弭是有欺骗性的。在《一只鸟的告别》中,主人公的多重自我被蒙太奇式地组织在画面中,赤裸身体被孤立出来而悬立于前,现实自我则漂浮在后,面孔原本遮蔽在一层浮动的青雾之下隐而不现,言语沉默,思维则寄托于飞鸟出走。在诱导下,观者将视线的流动停泊在对这一无时间性、无叙事性的图像的注视之上,画面内是被凝视着的自我,画面外则是目光的发出者——此时权力尚归观者所有。

然而,就在观者的视线被诱捕的时刻,艺术家决定使“她”苏醒,给予她向外凝视的眼睛。于是,她看向我们,我们也不得不迎击她的目光。本沉浸在审视与寻找视觉快感的观者意识到自己也可能被他者注视,便立即从一个主体变成了他者眼中的客体。如李佳琦所言,“我将人与自然置于编造的虚境中,通过凝视的主客体身份对调或制造凝视陷阱来诱捕其背后的真实,希望观者能从与画面的对视中产生共鸣。”

从丢勒的自画像到马奈的《奥林匹亚》,从德国表现主义到超现实主义再到波普,“回望的凝视”贯穿了艺术史中的诸多时刻,以或挑衅、或威慑、或引诱的目光目击了凝视客体的自我得以彰显,或凝视主体被迫揭示存在的诸多瞬间。萨特在《存在与虚无》中对“le regard”(看)进行了深入探讨。他认为,目光具有强大的力量,个体在被他人注视时,会感到深刻的暴露和脆弱,意识到自己成为了他人眼中的客体,而非独立的主体。这种凝视不仅是一种简单的看,更是一种能够影响和定义被观看者存在的力量。它揭示了他者对自我的权力,使个体意识到自己被物化,感受到自我被剥夺,进而促使个体反思自我存在的意义。

这种自我意识的外化过程使我们从“为自身而存在”(être-pour-soi)转变为“为他人而存在”(être-pour-autrui)。他者目光与评价所带来的对于自由与自主性的剥夺,便是“他人即地狱”之所在。被凝视者于是选择回望。他们由此不再只是被动的观察对象,而是主动参与到视线交流中。这种回望帮助被凝视者重新掌握自我感觉,从而避免被他者的目光所占有和定义。

“人作为一种群居动物,生于群体,必然产生在集体该如何自处的问题,这迫使我不停地寻找这个问题的答案。”

最初,李佳琦笔下的动物常有着象征含义,如《黑羊》代表着被排斥和孤立的自我,象征着在主流社会中无法被接受或理解的个体,整齐成列的白色羊群则象征着主流和规范,黑羊与之对立的存在打破了这种和谐,揭示了自我认同与社会认同之间的矛盾。又如《哑鸟》则象征了在社会环境与性别规训中被迫压抑与沉默的自我,虽然拥有飞翔的翅膀,但却被禁锢在无声的世界中。同样的,还有“盲牛”、“迷鹿”……它们均分离于某个自我意识受到挤压而游走的时刻,通过不同形式的对比刻画,自我也被不断探索和重新定义。

逐渐的,这些动物形象所承载的意义更为灵活和多样,也成为了艺术家与外部世界对话的图像媒介。在《黑手》中,她深有感于现实社会事件中的暴力行为与围观者的冷漠,用黑色将施暴者伸向无辜者的手描绘得尤为醒目和刺眼,从而直接控诉暴力行为;而围观者的黑色背影则暗示了社会的共犯心理,以及对弱者的漠视和忽略。与此相对的,她将受害者的形象替代成象征无辜和牺牲的羊,从而试图纾解视觉的直接暴力。

在“羊”模糊的头部轮廓上,艺术家再次为被动的客体赋予了面孔与凝视的目光。弱势者最后可以动用的力量,或许便是以一个回望微弱地还击。通过对凝视行为的刻画,她试图利用凝视者使被凝视者变成客体的权力,唤起一种道德和伦理关系。按照哲学家伊曼努尔·列维纳斯(Emmanuel Levinas)的观点,人脸意味着一道命令:汝不得杀戮(Thou shalt not kill)。与他者之面孔的遭遇成为一个伦理性事件,它命令主体被迫超越自身的利益,优先考虑他者的需求和权利。于是,这一回望的目光将我们推入一种伦理关系,它要求我们拒绝参与对弱者的谋杀,即不要忽略、漠视,要成为其伙伴,给予其尊重,它打破了自我中心主义,提醒观者在面对暴力和不公时,必须承担起对他者的无限责任。

动物是否拥有“面孔”? 或许在新作中,李佳琦也在延续与暗合着对列维纳斯的探讨。德里达在“动物故我在” (the animal that therefore I am)中,通过在赤裸状态下与猫相对而视的体验,表明动物也能通过其存在和凝视对人类主体产生影响,从而挑战了传统哲学中的人类与动物二元对立的观念,强调动物性是人类本质的一部分。

这个问题似乎过于复杂和富有争议,然而“马”确实在凝视着我们,“双双”(一头牛)在凝视着我们,在她的新作《水中月》中,“猴群”也在以其生动的面孔面向我们,以其无从回避的目光凝视着我们。如果说“猴子捞月”是以动物为喻体,对人类行为的象征性描绘,那么在这件作品中,人类中心的视角则被颠倒了,人们前仆后继地扑向水中月亮的倒影,而此刻轮到猴子以具有反讽意味的目光凝视着画面外的我们:“你以此刻所见为真实,抑或仅是自我的倒影?”

BONIAN SPACE is pleased to announce the first solo exhibition of artist Li Jiaqi, titled "With Open Eyes," running from July 20 to August 18. Curated by Gao Yumeng, the exhibition features over ten paintings created by the artist in recent years.

"When you look at me, I will also look at you with the same gaze." — Li Jiaqi

Gaze and Its Return

Li Jiaqi's creation begins with the "self" confronting internal contradictions and the complex external environment. She symbolically depicts the subconscious world with flowing lines and colors. The characters in her paintings peel away various forms of the self under the gaze of external others—isolated, suspended, struggling, and escaping—eventually dissipating into a suggestive fictional nature.

However, this subject's dissolution in complexity is deceptive. In A Bird's Farewell, the protagonist's multiple selves are montaged within the frame. The naked body is isolated and suspended in the foreground, while the realistic self floats behind. The face, initially veiled in a layer of floating cyan mist, remains hidden. Speech is silent, and thoughts are entrusted to the departing bird. Induced, the viewer's gaze flows and rests upon this timeless, narrative-less image. Inside the frame, the self is being gazed at, while outside, the gaze is cast by the viewer—the power thus far belongs to the viewer.

However, at the moment the viewer's gaze is captured, the artist decides to awaken "her," granting her eyes to gaze outward. Thus, she looks at us, and we are compelled to meet her gaze. The viewer, immersed in scrutinizing and seeking visual pleasure, realizes they too may be observed by others, transforming from a subject into an object in the eyes of another. As Li Jiaqi states, "I place people and nature in a fabricated virtual realm, using the role reversal of gaze subjects and objects or creating gaze traps to capture the truth behind it, hoping the viewer resonates with the confrontation with the painting."

From Dürer's self-portrait to Manet's Olympia, from German Expressionism to Surrealism and Pop Art, the "the return of the gaze" has traversed numerous moments in art history, witnessing the self of the gazed object being manifested through provocative, deterrent, or enticing eyes, or forcing the gazing subject to reveal existence. Sartre, in "Being and Nothingness," delves into "le regard" (the gaze). He believes that the gaze possesses immense power; when an individual is observed by others, they feel deeply exposed and vulnerable, realizing they have become an object in others' eyes rather than an independent subject. This gaze is not just a simple look but a force that can influence and define the existence of the observed. It reveals the other's power over the self, making the individual aware of being objectified, feeling deprived of self, prompting reflection on the meaning of their existence.

This externalization process of self-awareness shifts us from "being-for-itself" (être-pour-soi) to "being-for-others" (être-pour-autrui). The deprivation of freedom and autonomy brought by the gaze and judgment of the other is where "hell is other people." The gazed chooses to look back. They thus cease to be merely passive observation objects, actively participating in the visual exchange. This counter-gaze helps the gazed regain self-feeling, avoiding being possessed and defined by the other's gaze.

"Humans, as social animals, born in groups, inevitably face the question of how to position themselves in the collective, forcing me to continually seek answers to this question."

Initially, the animals in Li Jiaqi's works often have symbolic meanings. For example, Black Sheep represents the rejected and isolated self, symbolizing individuals who cannot be accepted or understood in mainstream society. The orderly white sheep symbolize the mainstream and norms, with the contrasting existence of the black sheep breaking this harmony, revealing the conflict between self-identity and social identity. Similarly, Mute Bird symbolizes the self forced into silence and suppression by social environment and gender norms, possessing wings for flight but trapped in a silent world. Likewise, there are the Blind Cow, Lost Deer... All separated at moments when self-consciousness is squeezed and wandering. Through contrasting portrayals in different forms, the self is continually explored and redefined.

Gradually, the meanings carried by these animal images become more flexible and diverse, serving as a medium for dialogue between the artist and the external world. In Black Hand, she deeply reflects on violent acts and the indifference of onlookers in social events, depicting the perpetrator's hand reaching toward the innocent in a particularly striking and glaring black, directly condemning the violence. The black backs of the onlookers imply societal complicity and indifference towards the weak. Conversely, she replaces the victim's image with a sheep symbolizing innocence and sacrifice, attempting to alleviate the visual violence.

In the blurred outline of the sheep's head, the artist once again endows the passive object with a face and a gaze. The weak may finally use a gaze to mildly counterattack. By depicting the act of gazing, she seeks to use the power of the gazer to turn the gazed into an object, evoking a moral and ethical relationship. According to philosopher Emmanuel Levinas, a face signifies a command: "Thou shalt not kill." Encountering the face of the other becomes an ethical event, compelling the subject to transcend their interests and prioritize the needs and rights of the other. This returning gaze pushes us into an ethical relationship, demanding we refuse to participate in the murder of the weak—not ignoring or neglecting them, but becoming their partners and giving them respect. It breaks down self-centeredness, reminding viewers to bear the infinite responsibility towards others when facing violence and injustice.

Do animals have "faces"? Perhaps in her new works, Li Jiaqi continues and echoes Levinas' exploration. Derrida, in "The Animal That Therefore I Am," through the experience of being naked in front of a cat, demonstrates that animals, through their existence and gaze, can influence the human subject, challenging the traditional philosophical dichotomy between humans and animals, emphasizing that animality is an essential part of humanity.

This question seems overly complex and controversial, yet "the horse" indeed gazes at us, "Shuangshuang" (a cow) gazes at us, and in her new work Moon in the Water, the monkey group" also faces us with their vivid faces, gazing at us with unavoidable eyes. If "Monkey Fishing for the Moon" uses animals as metaphors for human behavior, then in this work, the anthropocentric perspective is inverted. People rush towards the reflection of the moon in the water, while now it is the monkeys who gaze at us from the painting with a satirical look: "Do you see reality or merely your reflection?"