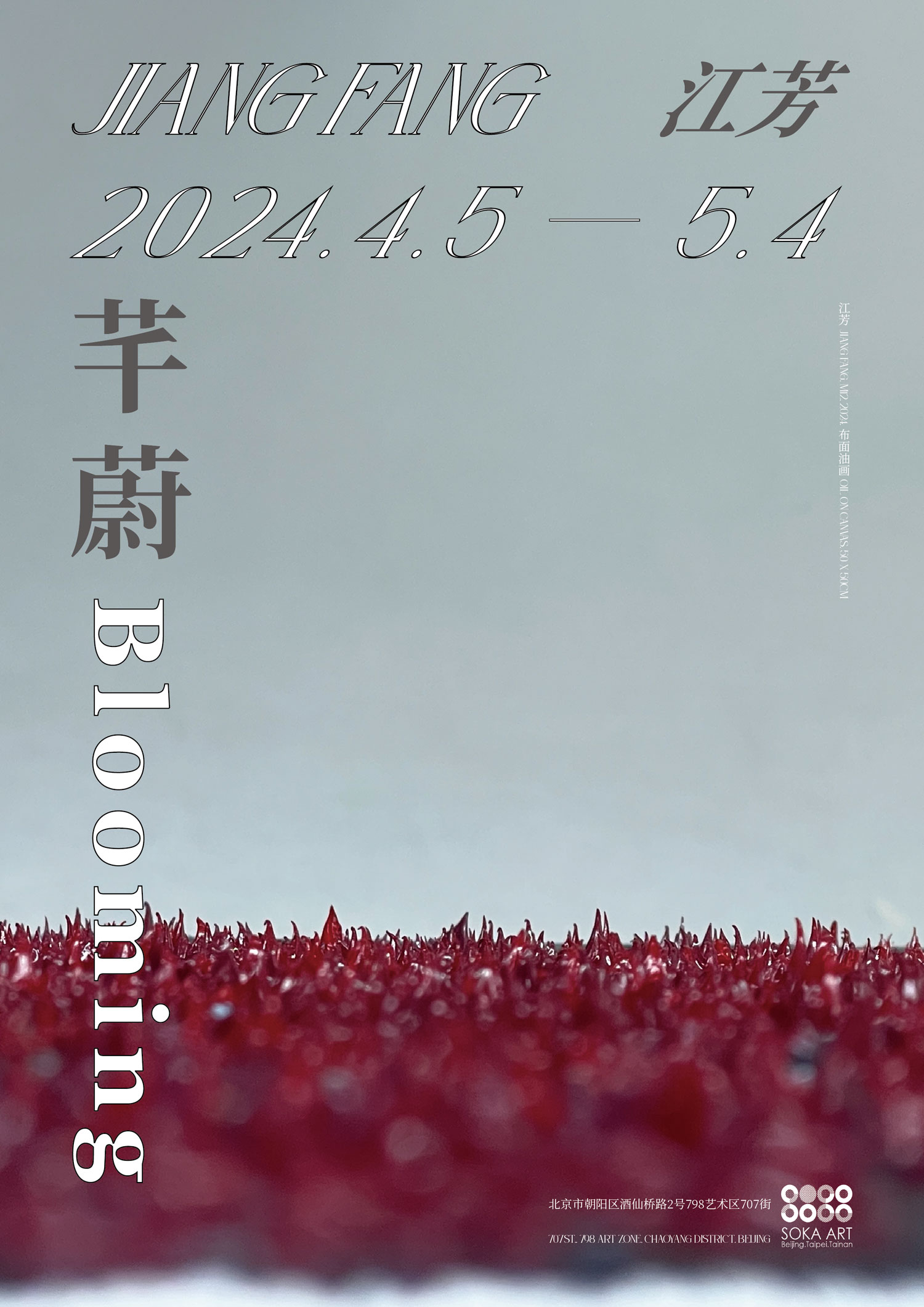

All the paintings in "Blooming" can, in a sense, be traced back to a chance encounter in 2014: during a material experiment, Jiang Fang pressed a piece of lace window screen flat against a thick layer of pigments and saw that the paint was squeezed out of the hollowed-out portion of the lace to form another scene, and that, under the light, these dense, prickly bumps stood up like a jungle growing out of the canvas. Prickly projections, as if they were jungles growing out of the canvas. From there, she tried to use a slightly thinner brush dipped in heavy paint to gradually "pull out" clumps of thorns one by one on the canvas and then scrape or thread them together until they formed a lace-like floral pattern. The pattern of the lace is continuous, regular, and artificial, while the "jungle" of pigments rising through the lace depends on too many uncontrollable and uncalculated "providences." just like natural plants, no one can know which beam of sunlight finally decides the leaves' Like a natural plant, no one can know which ray of the sun ultimately determines the closing of the leaves, the direction of the vines, and the bending of the branches. This duality of mutual fulfillment seems to point to a specific direction that she has been pursuing in her previous painting practice: using brushstrokes without representational function to shape paint into rows or circles of texture with strong tactile and episodic effects on the canvas. The lace experiment, however, injected a new logic of expression into these material textures, a pure form closer to reality: using "thorns" that are not tamed by the canvas plane to shape a "flower" that exists only in the world of images.

It is of course too simple to try to explain a decade-long line of paintings with a single event, but it does help us to see the artist's work clearly to a certain extent. In fact, before 2010, Jiang Fang had already been focusing on a kind of concrete abstraction that she called "traces": each brushstroke in the painting is not oriented towards an intended image or a real object, but rather, it is a diary-like presentation of the ups and downs of a period and emotions, which is faithful to the description of the following "The collision of a certain detail of life with a certain point of the inner world." "Traces" act as a visible anchor point between the world of painting and the world of life, and the materiality of pigment and the strong sense of texture provides the anchor point for the traces. What Jiang Fang seeks is not so much the lightness of imagination as a solid authenticity. It happens firstly in a tactile way. Starting from 2009, Jiang Fang tried to "pull out" the tips standing upright on the canvas with heavy paint, and the series of works in 2012 grouped these sharp or condensed tips into some regular shapes. The lace-inspired images of flowers further transform the abruptness and excitement that previously seemed to pierce through the canvas into a luxuriant appearance that resembles the growth of grass and trees. The pattern of the flowers is not so much the content of the paintings as it is the rhythm of the poem, which makes the words a poem but is not what the poem is about. Similarly, it is not the painting of a flower that is important. Still, the traces formed by the strokes, the movements, the paint acting on the picture and its rows, the irrigation and deposition of time, the growth and change, and here are some of the most basic answers to the most basic questions about painting, and at the same time the most personal and tangible ones.

"I owe you the truth in painting, and I will say it to you." But here, the surface of the canvas is the whole realm of truth. Color is color, and it leads only to pure pleasure. There are pinks and greens, somber blues and purples, radiant, bright yellows, untempered and eclectic, and by superimposition, variation, and thickness, this pleasure is sharpened or has a staccato quality. Flowers are more complex, but whether they are continuous and distributed like fabric or embroidery patterns, or whether they are threaded by dense rows or chains of winding curves, or whether they appear singly or in pairs, as if they had been drawn from a sketch or cut out of paper, they don't represent anything but themselves. They appear as if written on a loom or in a program code and always contain indigestible stones that interfere with the illusion of smoothness that the painting traditionally wishes to create. The painting here lays bare its most basic secrets, which must be made up of differences and repetitions of the most minor visible units. Like the rows of lines in a sketch, like the strokes of a chalk. Here, these most basic units of image stand up from the plane and repeatedly ask what makes a painting a painting, using continuous, dense, or scattered repetition, and the difference that depends on repetition. It is essential to know that when we look at a map, we only follow those curves and colors, those markers and notes in our mind to trace and imagine the ups and downs of the mountains, the twists and turns of the rivers, the deserts, and the jungles, the barren lands and the lush fields. If we get close enough and stay long enough in front of these paintings by Jiang Fang, we will find an actual terrain - real, not because these awns, scrapes, staccato, and textures correspond to a natural landscape, but because they exist as a real world. If one does not seek to recognize a flower from this canvas, then perhaps one can try to imagine twelve other ways of looking at a painting. In this sense, does the truth of painting mean that it lies only in the way the viewer wants to sign this contract of freedom?

Freedom is also something Jiang Fang pursues. Perhaps she knows too well how to "paint a picture," so she tries to get rid of that kind of watery, unthinking, vulgar talent, just like a poet who struggles to find a way to re-polish his language. On the blank linen, Jiang Fang paints like a farmer sowing seeds, or rather, sows the thorns of those brushstrokes with repetitive and patient labor. The brushstrokes are to be independent from a functional shrewdness or expressive panache, to make a world, or to make its surface, with their uprightness, clumping, emergence and spreading, iterations and echoes, repetitions and differences. Each brush stroke is like a thorn planted on the picture, and they may all become a trace. The painter's breath, his mind, and the passage of time are all buried inside. It can only be imagined and felt but cannot be restored to the flow of time. But it can re-emerge through a thorn and continue to grow. As a matter of fact, Jiang Fang has more than once referred to the image of "growth," in which there is a specific concession to chance, a certain confidence in painting. Still, perhaps it stems more from understanding the relationship between the person who paints and the painting. In an era where everyone can speak of the so-called "world image," is it still possible for a painting to refuse to be grasped as an image or an object? Is "growth" an opportunity to secretly overturn the so-called "subject-object" order and turn pictorial activities into genuine seed-sowing activities? Whether it comes from intuition or thought to a certain extent, Jiang Fang has turned "painting" into "not painting", and the making of images into sowing seeds, planting rice seedlings, loosening the soil, waiting, and nourishing. "To make the song move, to become a graft, without letting it become a (static) meaning, work or spectacle." Matter (its color, hardness, breath) is so grafted onto otherwise barren surfaces that, in our imagination, it takes on a temporal unfolding and change that generates a song.

Yet these do not imply a lack of the painterly or even quite the opposite. Especially in her recently completed works "Spring Breeze" and "M" series, the superposition and mottling of different color backgrounds, the rhythm of the picture stirred up by dense or sparse thorns, and the rich effects and texture created by the variations of flat painting, rubbing, scraping, etc., all of them have pushed the pleasure and joy that painting can promise to its extreme. Our minds, hearts, and senses are constantly activated and repeatedly agitated, like a musical instrument being played. It is the intensity of pure pleasure that is amplified by the reverberation obtained here. Every "trace," every tiny movement, every basic unit of form that creates this effect is still clearly recognizable on the canvas, not compromised or obscured by the "overall image." In this sense, perhaps Luc Nancy's description of the art of sketching can also be applied? "...... Its charm is due to a repeated birth, a continuous invention, a lifting up of ...... Thus, all the arts owe their pleasure to the desire projected on these endless traces! ".