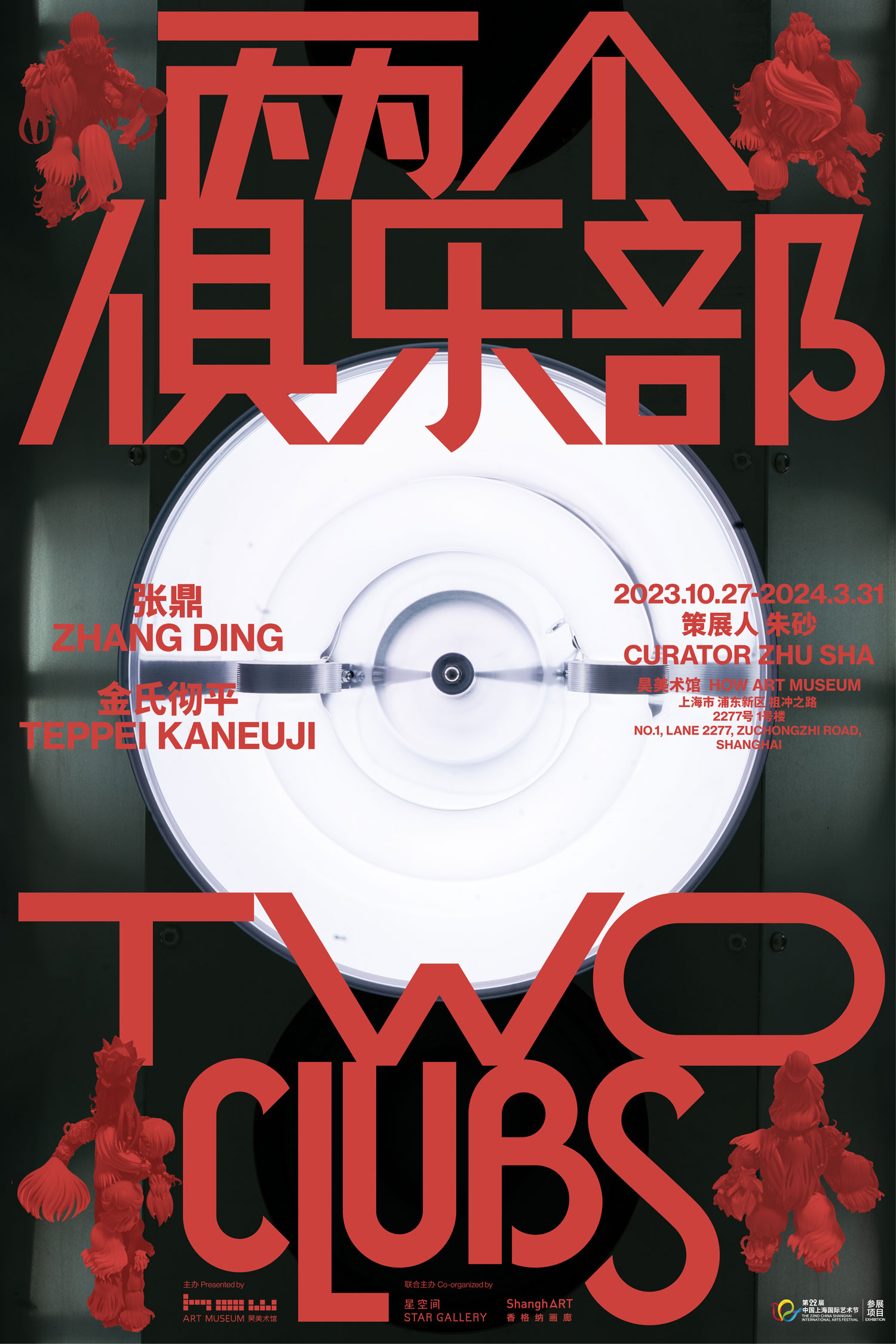

In the 5th century BC, the wooden grandstand sitting in the Athens marketplace collapsed, injuring some people in the process. Athenians analyzed the accident and decided to build a theater with stone on the southern slope of the Acropolis hill as an offering to the god of wine, and the theater was later known as the Theatre of Dionysus. In the two centuries thereafter, similar theaters started to appear in other Greek cities, forming the early form of performance viewing. The 20th century was one of rapid and exciting progress, during which theaters and art museums began to intermix. People still loved performing, and people enjoyed viewing; as viewing experiences continued to expand through various cultural movements, and concepts were borrowed and applied across disciplines, the theater space is now prevalent across society. Peter Brook extricated the concept of theater from traditional architecture and declared that any space can be used as a theater, while Andre Malraux’s Maison de la Culture made allies of a theater and a museum, linking the two and perhaps even equating them in a certain sense. Today’s artists no longer refer to theaters as such. They are referred to as clubs.

Zhang Ding has long held interest in clubs. His CON TROL CLUB first appeared in a 2013 piece—“It was a massive pagoda-shaped theater made from dozens of speakers that doubled as a complex audio-feedback device that samples the music it plays to be replayed at a higher pitch, eventually resulting in a mixture that sits squarely between music and noise.” This massive audio installation was first shown at UCCA’s ON/OFF in 2013, and then persisted at the Biennale de Lyon of that year, as well as the ShangART Taopu 2014 in Shanghai. In 2016, the CON TROL CLUB suddenly became an “artist label” of Zhang, who wrote in the official statement that “by integrating artists in various fields, geeks and musicians, CON TROL CLUB presents gatherings and parties in specific spaces with sound, immersive A/V installations, etc., to explore the dialectics of control/anti-control.” Since then, Zhang the artist has fashioned himself into a producer and a party organizer, which were further propagated through interviews and press releases found here and there.

In contrast, Teppei Keneuji’s Teenage Fan Club is a more lyrical expression. The artist states that in his earlier days of viewing performances, when he was usually relegated to the back, he could only watch the massive crowd standing between him and the performers. This personal experience was redirected into one of his most important collage installation series continuing to this day. Therefore, unlike the flamboyant one discussed earlier, the Teenage Fan Club is not only the extraction of an individual’s personal experience, but also an assemblage of the societal observations interpreted by contemporary art and pop culture. Kaneuji also advocates the act of performing as a clue of his art. For example, he collaborates with musicians in his White Discharge and frequently appears in theaters as a scenographer.

The ingenious game of identity and naming strategy, which were also used by the previous generation of artists, were considered entrepreneurial. Unlike their predecessors in ancient times, artists of today are no longer resigned to being considered as solitary horoes in the dark. After praising God, pleasing patrons, entertaining the court, and celebrating tribal military accomplishments for generations upon generations, artists started out towards personal expression, extricating themselves from public affairs and reducing their craft to a form of personal entertainment. It is not simply a word game: when the state attempts to discipline people’s views and opinions through free market mechanisms, artists will counter with the market to realize their own goals under cover, thus making identity politics unavoidable. Entrepreneurs wish to embrace a greater world beyond the transcendental private life and to generate more echoes in the public domain. So do our producer and scenographer, only in another outfit and posture to look different. If the last generation of artists have blurred the boundaries between artworks and products, high art and popular culture, art and day-to-day experience by using the name of “company”, “club” performs a similar task with equal inflammatory and seductive powers, less confrontational and banteringly. The Clubs have observed how people’s long-lasting ways of living have been inlayed deeply with revelry and entertainment, therefore they are a product of the custom, at once critical and practical. Be it a company, a club, or a studio, these names, or even slogans and paradigms, keep an arm away from each other in the iteration of systems, leaving significant influences during the inevitable struggles of every single replacement.

Zhang Ding’s latest piece Battery is a large-scale silicon installation that replicates a set of new energy vehicle batteries at 1:1 scale. Silicon, a new entry in Zhang’s vocabulary after machinery, metal and building stone, creates to some degree a skin texture of the work. Compared to his previous works, this latest installation carries a subtle psychological warmth. Hidden behind the artist’s characteristic evasive and obscure narrative style, Battery leads the viewer into an enormous alternative reality. Indeed, Zhang has never been confined to his earlier approach of pop art, nor has he opted for the plain and ungarnished style. Instead, he plots with a slew of exquisite craftsmanship. The audience will only sense the slightest eeriness after seeing through the artist’s layered application of materials and excessive use of matter, as well as his complicated onsite maneuvers. Thomas de Quincey and Jean Cocteau both compared literature to murder. Seeing it as bullfighting, Michel Leiris believes that while the artist does not face the risk of death as a real bullfighter, he or she can still “introduce a bull's horn into a work of literature if only as a cast shadow,” or a danger or tension in a positive sense. On that account, the artists today are situated in the middle of a push-and-pull tension between the ever-reverberating sensitivity and the ability to accurately assess the said sensitivity.

Comparatively, Kaneuji’s has a more active response towards the use of ready-mades and materials, or the unshakable reality so to speak. His latest work is built upon the form and language of the Teenage Fan Club, ant that is not by happenstance. The two artists’ different social environments have led to their different strategies. Under a broader sense of culture, they fight in the same trench; if nothing else, they both stand ambiguously against the West in a geographical sense, and both react to the application of technology, to Neo-capitalism, and to the world of consumerism and cultural industry in this time of raging yet hesitant historical transformation. People approach progressive and liberal views with caution and apprehension, doubting unitary systems and grandiose narratives, questioning classical notions of truth, rationality, identity, and objectivity, and in general stand against standards of enlightenment. The world as it is today is accidental, groundless, fickle, and uncertain, and therefore lacking depth or a center, devolving into a series of disparate cultures and interpretations. Artists, as a result, are also no longer acolytes of a single ideology. On the one hand, they despise the reality; on the other, they are part of it, not to mention the prolonged debate between good taste and popularity, the harsh struggle of gender identity, and the dual discipline of the market and rights. The complex and conflicting reality has led to this amalgamated state, placing artists in an irreplicable milieu. Such contemporary cultural form and style are at once fevered and intimidated, seemingly faithful yet dubious, interwoven with the market impacts and plenty other secular considerations. Artists no longer seek soul-searching debates; instead, they slowly fade away and find shelter behind various aliases.

Italo Calvino believes that there long exist two opposing tendencies: one turns language into a cloudy form like fine dust floating in the air, while the other gives language a certain weight and density. I dare not fully quote the metaphor of weightlessness and weightiness, just as I do not wish to refer to this exhibition as a “duo solo,” and I would never use “mid-career retrospect” either, even if these terms, objectively speaking, are appropriate in certain ways. So the Two Clubs can be seen as a juxtaposition of here and there, the public and the private, the secular and the divine—whether parallel or intersecting, they do not share the same destiny. There are also some culturally critical subjects that we are familiar with, or certain visions that are used as salvation. When theaters or clubs are taken as a paradigm, when youth and revelry become the language, the Messiah of today is revealed.