SHANGHAI—70 Square Metres is delighted to present Be My Guest. a group exhibition featuring four artists from Africa: Cornelius Annor (b. 1990, Ghana), Kingsley Dzade (b. 1989, Ghana), Wilfried Mbida (b. 1990, Cameroon), and Sphephelo Mnguni (South Africa), who share their stories of their identities, communities, and heritage. Their figurative works have themes that revolve around and celebrate societal and cultural situations that shape perceptions about living, including highlighting the dynamics of modernity and adaptability to the changes it ushers.

Cornelius Annor’s recollection of his personal experiences in Ghana and his background in photography provide the basis for his themes, such as “togetherness and intimacy within domestic and community spaces”. His painting Akwaaba (meaning “welcome home” or “welcome back” in Akan) relives a scenario where salutations and gestures of recognition (love, respect, and solidarity) were accorded to the majority of Ghana’s diaspora in the 1980s and 1990s upon their return to their native land. The artist’s use of traditional Ghanaian textiles to form textured patterns in his work creates an atmosphere of layered memories, emotions, and experiences. Family intimacy and cooperation amongst members is the preoccupation of his painting titled Ma Ye Nkasa, meaning “let’s talk”.

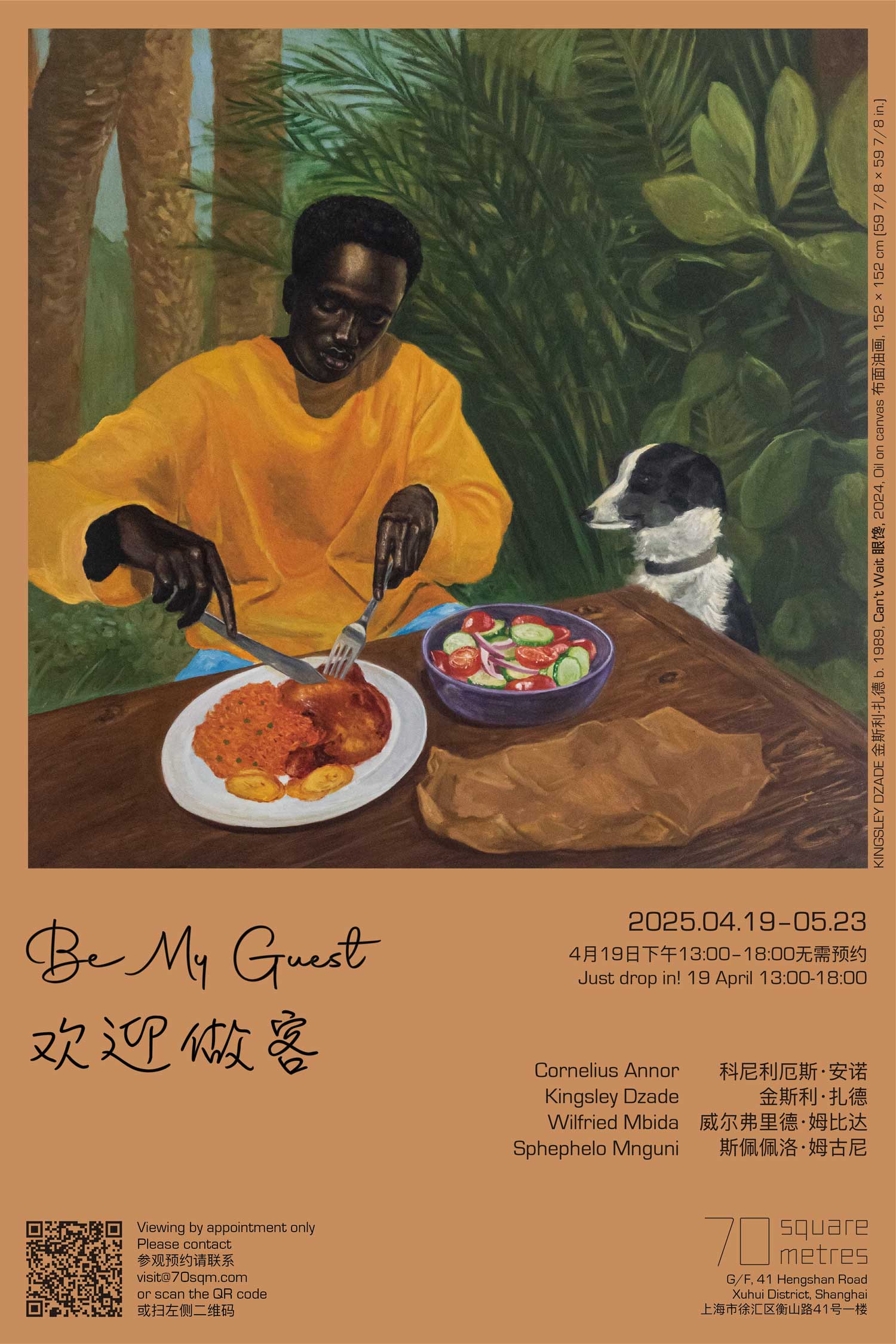

Set in his native Ghana, Kingsley Dzade’s paintings highlight his favourite dishes, employing food, central to the survival of humanity, to weave a compelling narrative of national identity, communal bonding, and cultural exchange. Commensality—the act of eating together—becomes a perspective of evaluating how food engages cultures and encourages viewers to reflect on the complex ways in which eating habits are tied to identity. In One Man No Chop, which refers to the Ghanaian phrase emphasising the importance of sharing and togetherness, Dzade appraises the integral role of food and commensality in building relationships at social gatherings such as weddings and funerals.

Consumerism, global influence, and layers of health issues are suggested in Self-Treat where an overweight African lady at a table consumes several pastries and junk food including pizza, a couple bottles of Coke, a container of ice cream, and doughnuts. It is understandable how she has gotten bloated and is at risk for a diabetic episode. In Favourite Dish I, a female subject drinks water from a nylon wrap, while carrying a plate of what appears to be a favourite traditional meal. Urbanisation has brought about on-the-go fast food packaged in disposable materials hazardous to the environment. This development is prevalent not only in Ghana but also in Nigeria amongst other West African countries. Conversely, we see a restoration of healthy eating and living in the organic setting of Can’t Wait, where natural vegetables are served in a bowl and consumed alongside a wholesome meal. A dog at the table side provides company that hints at collectiveness and sharing.

Wilfried Mbida aims to immerse the viewer into the beauty and tranquillity of her environment. La mamelle portrays a room in a home in Central Cameroon, which appears to be a kitchen, where shiny steel pots and bowls are shelved. The main subject is a female, identified by the artist as the younger sister of the lady of the house, staring out the window from which daylight illuminates the otherwise subdued dark interior. This silent mood coupled with the dark ambience is borne out of the artist’s experience of the lack of electricity in the community, a salient social commentary. Tuborg presents a modern living room where an elderly figure lays on a sofa, while a child stares out a window. The image on the television contributes more vitality to the ambience, which was lacking in other paintings where there appeared to be no electricity. The juxtaposition of the subjects here is vital in depicting the political situation in Africa at the time.

Sphephelo Mnguni’s presumptions are that“one can tell a great deal about a people by what they deem important enough to remember, to create moments for, and what they celebrate.”The artist therefore reviews narratives of Blackness through portraiture and their innateness, echoing the positivity of black culture within contemporary discourse. Through daily living and observation, the artist interrogates feelings of a permanent state of hybridity between cultures, places, and identities. Mnguni’s Izimpande: The Roots depicts a modern setting with a goat in view. The cultural significance of a goat as a sacrificial offering to God in a modernised space improvises a dialogue merging identities of traditional African culture and contemporary developments. In Cinga: Portrait of a Giant, Mnguni pays homage to an important contemporary artist for his contributions to the South African art industry. His portraits of black personalities are to be appreciated for their beauty and not viewed in a colonial subjective frame. Mnguni’s work explores an emerging African modernity underpinned by an urban black experience and visual culture.