The bonfire on the drifting ice illuminates a strange world: a hunter lowers his gaze to the arrow about to be released, carefully assessing its accuracy; a raven perches on a withered branch, looking back at its companions still circling above; as if an uprooted land were submerged in seawater, the distant mountain contours glow with a light that seems to waver between dusk and dawn… This is the “Wilderness” as depicted by Li Wendong.

If the traditional landscape world was the aspirational retreat of scholars and hermits, then the realm illuminated by the firelight in this painting reveals a parallel world overlooked by historical narratives. It does not stem from an archaeological impulse, but rather, is annotated through imagination—an artist of today recalling the fate of a frontier hunter.

Li Wendong, employing a combination of tempera and fresco techniques, repeatedly rewrites the narratives within his paintings, becoming the creator of the history depicted within them. The disappearance of an elephant in one place may, perhaps, signify the emergence of a horse in another trace.

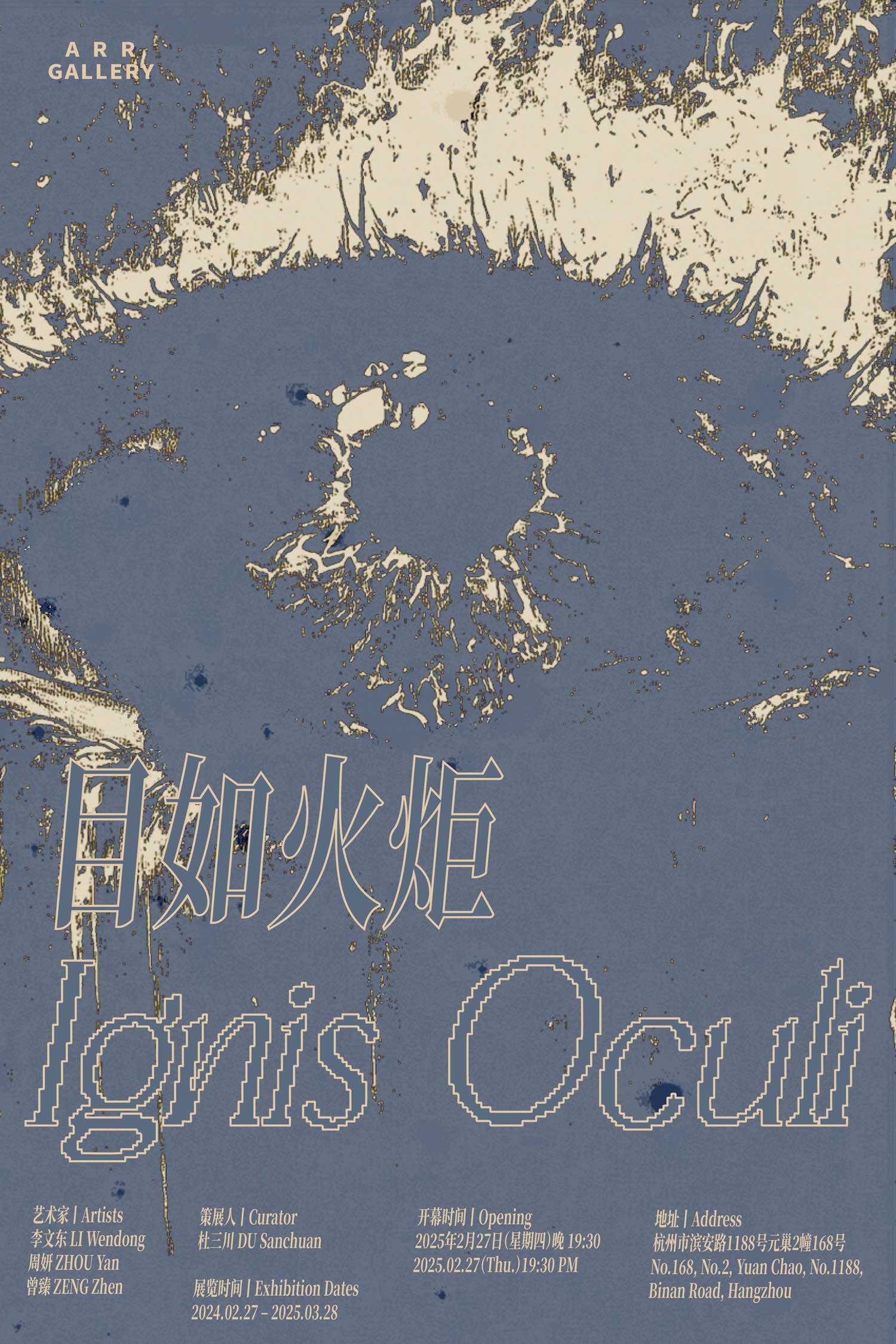

“Fire” is a primordial metaphor for human civilization. In Zhou Yan’s paintings, it manifests as an event through its own movement within the composition. What it anchors is the moment in which a state of contemplation occurs—where contemplation itself becomes an established fact, rather than emerging from any narrative impulse driven by motivation.

The artist moves through the fluid states of emotion with an almost analytical gaze, and the imagery in the paintings serves as both a response and a revelation. Whether it be the traces of something burned or more tangible objects—bark, candles, flesh, or teeth—they evoke a state of gazing that transcends the construction of visual meaning. This gaze refines painting into an alchemical elixir for cognitive reconfiguration, becoming an archaeological inquiry of knowledge initiated and enacted by the artist upon the self.

Whether in the archaeological excavation of knowledge or in artistic creation, neither serves as a tool for historical research here—instead, they become the gunpowder that detonates conventional cognition. As we discuss “depression” in WeChat articles, search for “criminal tendencies” through genetic testing, or define the “normal person” via AI algorithms, the ghost of Foucault lingers, reminding us that every seemingly neutral discourse may conceal the motives of power.

To dismantle this latent discipline, one must first become an archaeologist of one’s own history—excavating counter-memories buried beneath dominant narratives in the fractures of discourse. In Zeng Zhen’s work, digitally constructed faces replace religious icons and ideological deifications. These figures do not refer to specific identities; rather, they are images ruptured by the artist’s gaze, revealing the fragmented remnants of discursive construction. In an era where historical nihilism spreads unchecked, this act signals a dangerous hope: an explosion, followed by a learned attentiveness to the fissures—an act of rebellion and transgression against cultural codes, reclaiming the power to reconstruct historical narratives in the present.

文/三川

译/照居