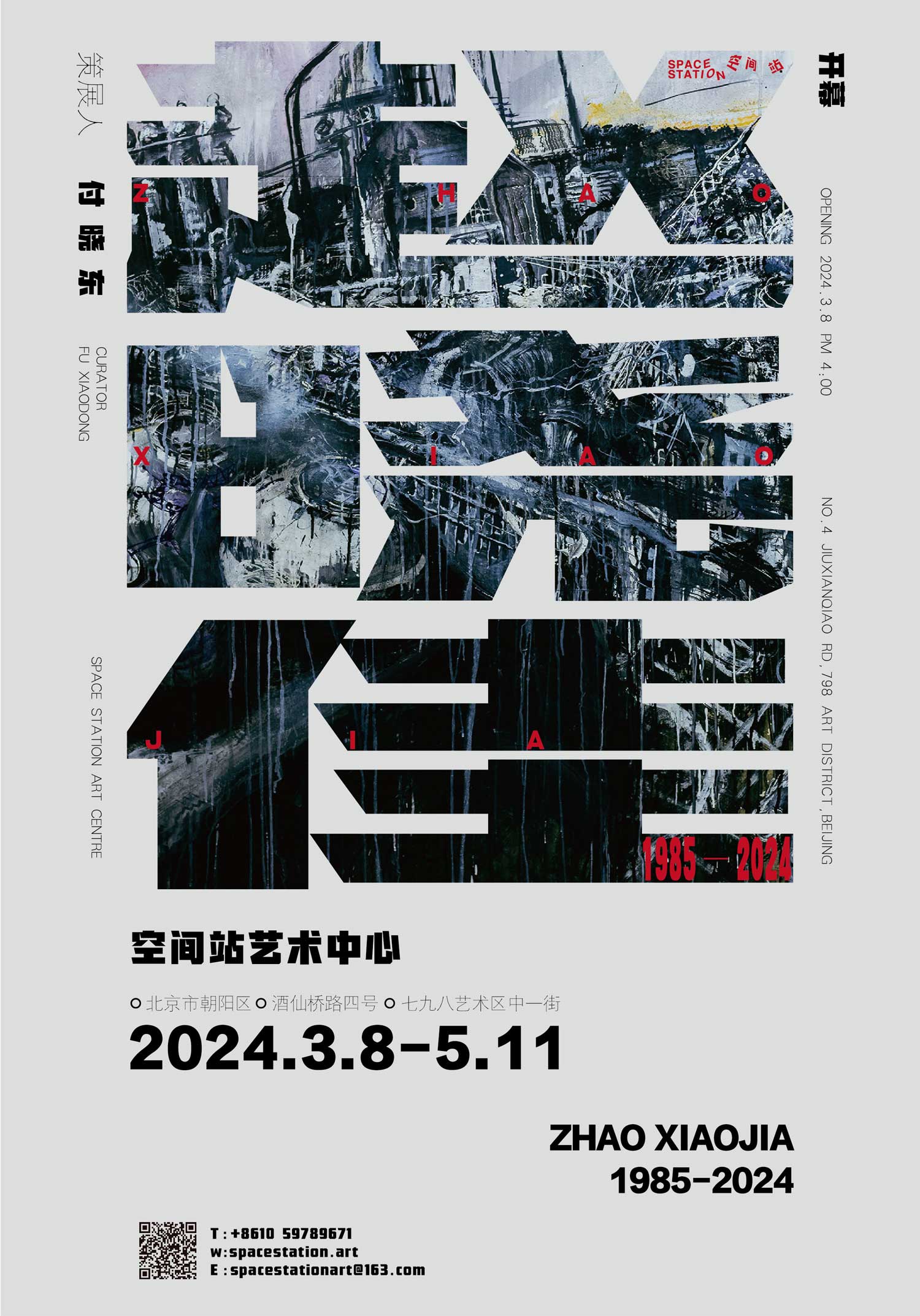

展期 Period:

2024.3.8—2024.5.11

艺术家 Artist:

策展人 Curator:

地点 Venue:

策展人文章 Curator's Article:

《寂寞大工厂:浅谈赵晓佳的油画》

文/付晓东

赵晓佳在鲁迅美术学院出名得特别早,我还是美院学生的时候,就看见略显冷峻的他站在舞台上给大家表演摇滚乐,同学们都说他是油画系最有才华的师兄,代表作就是他最早开始画的那些尺幅巨大的《寂寞大工厂》。

赵晓佳从20世纪90年代就开始用巨大尺幅的黑白为主的油画描述东北重工业辉煌时代的落幕。大规模的拆迁成为我们那个时代的主题,恢宏浩大、歇斯底里,而又伤感沉重。赵晓佳用他挥洒的才气和充满生机的表达搭住了那个时代场景的脉搏。东北大工厂由辉煌转向颓废到过渡时期,正是赵晓佳90年代画的《大工业城市》那般,明快的色彩和抽象的分割结构呈现着秩序井然的城市空间,但远处的烟囱和压抑的天气隐含着即将到来的不安。辉煌是中华人民共和国成立初期对于大工业和矿产资源丰富的依赖,所谓共和国长子的情殇,工业文化象征着现代化文明和英雄主义的气质,经常听到“在50年代沈阳就如同八九十年代的上海”这样的比喻。这里面包括国有企业的私有化转型产生了大规模失去劳保和集体生活的下岗工人,他们从地位优越的国有体制的铁饭碗变成体制变革的失意者、政治上的失语者、社会上的边缘者,在现实的挤压之下过着从头再来、苦中作乐的生活。

升高,而后落下。曾经对未来群情激昂的超英赶美的工业化希望,如今已是破败、逼仄、腐烂的被摧毁的现实废墟。东北作为现实最早崩溃的精神征候,一代人的精神创伤图景,溃败的历史宿命,赵晓佳准确地选择了大工厂的废墟作为系列作品的母题。曾经乌托邦式的社会集体大工业生产的表征—大工厂,向外部世界释放出的梦幻般的神话空间被击溃,原来具有功能性的宏大庄严的厂房突然丧失了原有奇观式的荣光,成为只具备审美功能的精神创痛的在地象征物,成为现实悲剧的回不去的家园。在《大工厂》系列中,充满机器的厂房被搅拌在一起,升腾着烟雾,仿佛是一个由零件混杂而成的巨大的有机体,在毁灭的末期燃烧着自己的生命。其间的白色纤细线条如神经网络般飞舞,电线如脐带般纠缠,流淌泼溅的颜料与迅疾有力的出笔,形成了复杂而浑厚的钢铁之躯。

虽然出生于20世纪70年代早期,但是赵晓佳所关注的尺度并非70年代艺术家所共通的那种自我的私人青春期忧伤,而是更加恢宏的社会政治体制转型所带来的集体记忆的创伤和撕裂。理想的重构、自我的和解、家园的回归,成为急迫地抚平精神创痛的主题。工业气息的熏染也使东北的在地性和时代独特的烙印深刻地嵌在作品中,这片土地之上徘徊不去的情绪,辉煌与毁灭、彷徨与伤感、压抑与释放、意志与悲怆,如史书般如实地记录在了画面之上。

<The Silent Big Factories: An Introduction to Zhao Xiaojia’s Oil Paintings>

By Fu Xiaodong

Since the 1990s, Zhao has been using huge black-and-white oil paintings to depict the end of the glorious era of heavy industry in Northeast China. In those days, large-scale demolition became the subject matter, magnificent, hysterical, and sad. Zhao has caught the pulse of the scene with his talent and vibrant expression. The transition of those big factories in Northeast China from splendor to decadence is exactly like Zhao’s The Large Industrial City painted in the 1990s, where bright colors and abstract segmented structures present a well-ordered urban space, but the distant chimneys and depressing weather imply an impending uneasiness. The glory of the early years of the People’s Republic of China was its reliance on heavy industry and mineral resources, the so-called sorrow spot of the eldest son of the Republic. Industrial culture symbolized modern civilization and heroism, and it was common to hear metaphors such as “Shenyang in the 1950s was like Shanghai in the 1980s and 1990s”. This modernization process included the privatization of state-owned enterprises, which resulted in a loss of labor insurance and collective life for massive laid-off workers, who were transformed from holding a lifelong secure job in the state-owned enterprises into the disillusioned, politically inarticulate, and socially marginalized by the change of the system, and lived a life of starting over and enjoying themselves under the crushing pressure of reality.

Rise and fall. The industrialized hope of surpassing the United Kingdom and catching up with the United States, which used to be so excited about the future, is now a dilapidated, cramped, and decaying ruin of the destroyed reality. Since the Northeast is taken as a spiritual sign of the collapse of reality, the mental trauma of a generation, and the historical destiny, Zhao accurately chose the ruins of factories as the motif of the series. The fantastic and mythical space released by the utopian symbol of collective social and industrial production, the big factories, to the outside world has been crushed, and the functional grand and solemn factory building has suddenly lost its spectacle-like glory and become an on-site symbol of spiritual trauma with only aesthetic function, an unreturnable homeland for the tragedy of reality. In the series of The Big Factories, the factory building full of machines is stirred together, rising with smoke, as if it is a huge organism made of mixed parts, burning its life at the end of destruction. Among them, thin white lines flutter like a neural network, and wires are entangled like umbilical cords, and splashes of paint and swift, powerful brushstrokes form a complex, thick body of steel.

Born as in the early 1970s, Zhao’s concern is not the private adolescent sorrow that was common to artists of the 1970s, but rather the more grandiose trauma and tearing of collective memories brought about by the transformation of the socio-political system. The reconstruction of ideals, the reconciliation of the self, and the return of the homeland have become the themes that urgently soothe the pain of spiritual trauma. The industrial atmosphere has also made the uniqueness of the Northeast’s localities deeply embedded in his works, and the sentiments hovering over this land, such as splendor and destruction, uncertainty and sadness, suppression and release, will and pathos, are faithfully recorded on the paintings like a history.